National Democratic Revolution, Part 3

Worker-Peasant

Monument, Moscow

National-Scale Democracy

We have founded this study of the National Democratic

Revolution (NDR) on the practical necessity, as well as the historical fact, of

class alliance, and most pointedly on Lenin’s report to the 2CCI on 26 July

1920, on the National and Colonial Question.

A class alliance, or in other words a popular front, or a

unity-in-action, was always necessary for the defeat of colonialism. Such class

alliances were successfully put together in many countries,

including South Africa, as the tactical road to strategic political

independence.

Such an alliance is what is broadly known as a National

Liberation Movement. What the movement is supposed to do is called the National

Democratic Revolution. As much as it was nationalist, the anti-colonial

liberation movement was equally international in character. The Worker-Peasant

Alliance (hammer and sickle) is not just a Russian thing. It is universal.

The NDR’s international dimension is solidarity with the

National Liberation struggles of others, in the common fight against

Imperialism.

Expansion of

democracy

The National Democratic Revolution’s national dimension was

the enlargement of democracy. This the Imperialists invariably opposed with

divide-and-rule schemes of provincial federation, regionalism, “Balkanisation” et cetera. Hence the continuing struggle

against Provincialism, and the on-going defence of Provincialism by the

reactionary remnants in our country, South Africa, today.

We now need to look specifically at the expansion of

democracy to the national level. Why? Because, for revolutionary purposes, the

entire working class, and the entirety of the allied classes, must unite all of

their potential support, in numerical, and in territorial terms. This is a

practical necessity, if the liberation forces are to defeat the

well-concentrated class enemy, which is the monopoly and Imperialist-allied

bourgeoisie.

The battle to spread democracy to the farthest corners of

the country, and to the whole population in terms of class, race and gender, is

also the battle against regional and ethnic chauvinism. This effort aims to

create a centralised parliamentary democracy, or democratic republic, even if,

as Lenin pointed out in the report to the 2CCI, such a democratic republic can

only be bourgeois in nature - at first.

The structure of parliamentary democracy (i.e. the

democratic republic) is the organising scheme within which the polity at the

national scale is conceived and arranged. It is not sufficient in itself. It is

a shell that must be populated with organised elements, elements which must

also be extended to the national scale, just as much as the parliamentary

franchise is.

Among these organised elements are:

- The mass movement of national

liberation

- The vanguard party of the

working class

- The national (industrial) trade

unions and their national centre

- Class-conscious national media

of communication

- Many mass organisations at the

national level, including Womens’ and Youth organisations.

Communists can be found organising, educating and

mobilising, as is their duty according to the SACP Constitution, in all of

these areas, and this has been the case throughout the 90 years of the Party’s

life. The texts that are collected together in the linked document below

clearly demonstrate that the communists, even before the formation of the

Party, were concerned with the extension of organisation to all parts of the

population.

Early years of the Communist Party of South

Africa and the ANC

The attached document, which is itself a compilation, shows

that one predominately-white precursor of the Party was acutely aware that its

own aspirations could not be fulfilled unless the Black Proletariat was

mobilised to take the lead in the struggle. This was the International

Socialist League. It, like Lenin, had opposed the Imperialist war that broke

out in 1914. It was later to become a component part of the Communist Party of

South Africa (CPSA) on its formation in 1921. “No Labour Movement without the

Black Proletariat,” it said.

After its 1921 formation, the Party quickly became

predominantly black in membership, and the black cadres soon exercised a

leading role in mass organisations, of which the biggest, in the 1920s, was the

Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union (ICU), formed in 1919. Note that the (white) Labour Party had been

formed in 1908, and the African National Congress in 1912.

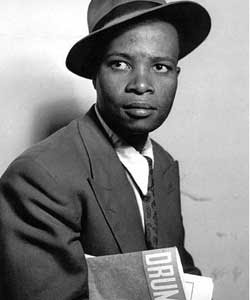

The expulsion of communists from the ICU, and in particular

of J.A. (Jimmy) La Guma, ICU General

Secretary; E.J. Khaile, ICU

Financial Secretary and John Gomas,

Cape Provincial Secretary, was a set-back for the working class and as it

turned out, it was fatal for the ICU. This episode is also recorded in the attached

document.

In 1927 Josia Gumede

was elected ANC President and he travelled to meet the top leadership of the

Soviet Union. That year was the tenth anniversary of the Russian revolution. He

travelled with Jimmy La Guma, a member of the party, secretary of an ANC branch

in Cape Town and a recently-expelled leader of the Industrial and

Commercial Workers Union (ICU). La Guma was expelled by the ICU together with

E.J Khaile for being communists. In that very same year Khaile was elected

Secretary-General of the ANC at its national conference in 1927.

The CPSA and the ANC drew closer together, though not

without problems. But the alliance was endorsed by the Sixth Comintern Congress

in the famous “Black Republic Thesis”

resolution, which said among others:

“The Party

should pay particular attention to the embryonic national organisations among

the natives, such as the African

National Congress. The Party, while retaining its full independence, should

participate in these organisations, should seek to broaden and extend their

activity…

“In the

field of trade union work the Party must consider that its main task consists

in the organisation of the native workers into trade unions as well as

propaganda and work for the setting up of a South African trade union centre

embracing black and white workers.

“The Communist Party cannot confine

itself to the general slogan of ‘Let there be no whites and no

blacks'. The Communist Party must understand the revolutionary importance of

the national and agrarian questions.

“A correct

formulation of this task and intensive propagation of the chief slogan of

a native republic will result not in the alienation of the

white workers from the Communist Party, not in segregation of the natives, but,

on the contrary, in the building up of a solid united front of all toilers

against capitalism and imperialism.”

In the attached document, the Comintern resolution is

followed by the famous Cradock Letter

written by Moses Kotane in 1934, five years before he became General Secretary

of the Party. It called for the “Africanisation or Afrikanisation” of the CPSA,

something that had clearly not yet fully taken place in 1934, five years after

the adoption of the “Black Republic Thesis”.

The story

continues in the next instalment.